The huge potential of Indian tourism and why it stands unrealised

By

Surya Kanegaonkar

| 5 Oct 2020

By Surya Kanegaonkar | 5 Oct 2020

India is yearning to realise its potential as a leading destination on the global tourist heatmap and envisaging Uttar Pradesh (UP) and Bihar – states that have lagged on a infrastructure and HDI metrics for decades – as host to a thriving hospitality industry in the 21 st century requires a carefully calibrated bottom-up approach, one that addresses multiple key areas. While on the surface, clear

benefits accrue, actualising the obvious commercial opportunity, deeper value lies in the synthesis of ideas emanating from the ensuing cultural interaction and knowledge exchange. While efforts are on to turn the densely populated Hindi heartland into an economic workhorse, one that is capable of facilitating significant tourist footfall, much ground needs to be covered in

infrastructure and human capital development.

Crunching the numbers

Ranked 34th in the 2019 Global Tourism Index and 7th in the Asia-Pacific Region, India has seen international arrivals grow between ca. 4-7% annually over the last 5 years – slightly above the 5.2% global growth rate – reaching 17.42 million last year, according to the Ministry of Tourism.Excluding non-resident Indians (39%) and visitors from South Asian nations (16%), the number stands near 8 million.

Despite the growth in international arrivals, India’s share of total foreign tourist arrivals is a meagre 1.24%, ranked 22nd in the world, contributing around $28.6 billion, or 2% of global tourism receipts. Domestic tourism has grown in the healthy low-double digits annually over the same period, correlating with the rise in purchasing power of the middle class intersecting with better domestic transport infrastructure.

Interestingly, the average duration of a visit is around 22.7 days despite 38% of international visitors entering the country for non-leisure purposes. Taking into account the average length of stay at a hotel of 2.7 days and adjusting for the fact that over 13% of foreign passport-holding tourists are of Indian descent and possibly visiting family, it could be inferred that on an average a tourist visits

5-8 locations in the country. The highest growth rates in footfall – up to 40% – have been seen in the Northeast, a region that has made significant strides in road and air connectivity over the past 4 years. Meanwhile, traditionally tourist-friendly states in India’s south have also retained their market share of tourist footfall and revenues.

Infrastructure to your doorstep

Short hop flights

Minimizing the time and cost of travel encourages visitors to explore more sites, contributing to tour operators’ top line and giving a fillip to the local economy. An extra 10-15% of time to spend on new site visits has the potential to add over $2 billion a year in revenues with current footfall numbers. This is not including a multiplier effect which could result in far greater revenue, as the benefits of

higher efficiency draw a greater number of tourists, both from the leisure and business segments.

In this context, development of international airports in Ayodhya and Kushinagar – the respective nodal points of the Ramayana and Buddhist Circuits – are steps in the right direction. A concerted follow-up effort would be required to incentivise airlines to operate on the 18 routes cleared for the Kushinagar Airport located 55 kilometres from Gorakhpur, the Chief Minister’s home constituency.

The success of this project is as much an economic matter is it is a political one, and its opening two months from now would mark an important milestone in the temple town’s history. Taking the cue from Gaya, an important Buddhist centre, Kushnigar’s immediate outreach would likely be to Southeast Asia, with Sri Lanka added to the list, the UDAN scheme will connect it to Lucknow and Gaya, while private airlines would link it to metropolitan cities. A similar model is likely to be adopted for the Ayodhya airport, while a total of 18 new routes connect cultural centres like Shravasti, Varanasi, Prayagraj and Chitrakoot amongst others under the UDAN 4.0 scheme.

Yet, the rosy outlook comes with caveats. While on one side, Indian airport infrastructure development is expected to get a $20 billion investment boost over the next 5 years, lessons from the past must be learned. Underutilization of capacity has often been as much a function of low ticket-demand as it is of airlines’ unwillingness to operate on the given routes. To fix this, the government can introduce subsidies for airlines on specific cost components of their value chain and fit airports with essential navigational aids that enable planes to land amidst low visibility, ensuring year-round operability.

The road ahead

Beyond airports, resilient road connectivity will underpin both last-mile and intercity travel efficiency. With the Prime Minister unveiling a $2 billion package for Bihar in the run up to the state elections, the government would be well placed to learn from problems faced in existing projects. Currently, the 100-kilometre road linking Gaya to Patna takes over four hours to cover when it should be taking an hour and a half, as contractors pulled out mid-construction.

Inter-department communication has been slow, miring progress, and must be improved for the upcoming Rajauli-Bakhtiyarpur, Narayanpur-Purnia and Aarah-Mohinia national highways. Best practices can be learned from the effective coordination between the environment ministry, road ministry and local authorities from nearby Madhya Pradesh which recently saw the successful completion of 37-kilometre elevated expressway, stretching through the Pench Tiger Reserve.

The National Infrastructure Pipeline (NIP) is being doubled down on by the government to run a fiscal stimulus-driven economic recovery. Amongst the important projects in the works are the 192-kilometre Ayodhya-Varanasi, 594-kilometre Meerut-Prayagraj and 296-kilometre Chitrakoot-Etawah expressways. Reducing travel time by 30-40%, the multibillion-dollar projects will nudge tourists towards using multiple air-connected nodes as bases for day trips to nearby sites. Hospitality industry workers would be able to travel to work from further afield where purchasing power is higher in comparison with urban areas, thereby reducing feedthrough costs to hotels which can pass on the financial benefit to visitors.

UP, a state with a population of 237 million and a per capita GDP of around $1,000, will be largely dependent on creating a circular economy while it industrialises, and a tourism economy as it modernises. Much of the early heavy lifting for utilization of new infrastructure projects will rest with the top 10% cross section of the population. Local tourism – which contributes to 80% of hotel occupancy – is growing at a rate of 12% and industry analysts expect this growth rate to double by 2023 once most of the main connectivity projects are complete. Yet, capacity building in the hospitality sector will continue to depend on the upper tenth of the state’s income generators, and for this to be materially significant, the economy must fire on all cylinders.

As old cities hope to gain a new look as they arrive prominently on the tourist trail, they get a chance to create an eco-friendly local economy that delivers world class sanitation and healthcare facilities from the get-go. Much like the Thai and Chinese models which involve the provision of piped water and subsidized yet high quality medical care, Indian towns can build spare capacity for both, with future projected urbanization in mind. Meticulous planning can guarantee seamless coordination between departments to get road, rail, electrification, gas piping and waste management projects working in lockstep.

Knowledge is power

Tapping talent

Quality human capital forms the bedrock of a tourist-friendly society. While some business leaders cite a severe shortage of skilled manpower in which only 9% of the required labour is in supply, others opine about a lack of a pipeline of university talent that would take up guest-servicing roles in fast-growing tier II and tier III cities. Outdated syllabi are being taught by a growing number of under experienced academics and consequently, the sector is increasingly dependent on inadequately prepared entry-level professionals who have been not been exposed to multidisciplinary teaching. The neglect of critical areas such as technology adoption and leadership, in a hyper-competitive industry with high attrition rates, has given rise to the need for practical upskilling through collaboration between industry and academia.

The National Council for Hotel Management & Catering Technology, which regulates 11 programmes from craftsmanship courses to master’s degrees, has succeeded in placing north of 10,000 students a year. However, with 2.4 million involved just in the formal sector, the additional numbers are falling short of fresh demand and attrition replacement. Furthermore, the uncertainty in the industry caused by the Covid-19 pandemic has dented enrolment interest, further complicating matters for hotels.

A determined effort to provide school-leavers with internships and short courses designed by industry experts, will go a long way to fill the skill gap. State accreditation of more programmes run by private colleges will provide students with a sense of security while e-learning reduces part of the upfront cost for students. In the case of UP and the wider Hindi belt, the colleges in cities that host tourist sites in the vicinity would be well placed to develop local talent as it mitigates the risk of region-based skill scarcity.

Cultural education

While the hospitality sector can find targeted solutions to deliver on specific end-user needs, success across the spectrum will largely be derived from cultural education and empowerment of local communities. Over 90% of tour operators, guides and providers of ancillary services would come from within the state, out of whom at least 85% are likely to be residents of the district hosting the heritage site. To help guests appreciate the unifying cultural thread that binds the town with places afar, client-facing personnel would benefit from a structured training programme that focuses on comprehensive study of philosophy, history, architecture, music and the arts. Additionally, pan-country site visits would help them bring to life the tenets that continue to define Indian society even today, and better equip the storytellers whose responsibility it is to elucidate to an overseas audience on how the site in focus, nestles into the broader Indic fold.

To bring forth the value of intercultural engagement on the back of tourism, it becomes imperative to educate communities about and sensitize them to, foreign cultures. Going a long way to enhance comfort for both the hosts and the visitors, bridging communication gaps both widens the scope for engagement and deepens the cross-cultural experience, giving rise to opportunities for constructive dialogue.

In this context, the under-construction exhibition and conference centres in Varanasi and Gaya can assert themselves as vibrant centres for knowledge exchange if, over time, they attract locals from all walks of life. True inclusivity will arise from multi-lingual interdisciplinary education at the grassroots level, starting from school, and should not be ignored at the expense of tertiary education reforms made to satisfy immediate skill gaps in the broader tourism sector. Special attention must be paid to customizing syllabi to emphasize on local, national and international cultures in equal measure, in context of the city’s place on the tourist circuit.

Show me the money

With the Indian economy under stress, reeling from Covid-19 and dealing with both internal and external challenges, questions arise as to how the growing funding gap for government’s plans will be filled. S675 billion of the $1.5 trillion NIP is expected to be funded from the budget and $465 billion raised from NBFCs, local bond issuances and bank loans. The balance will be dependent on international bonds and convertibles, sovereign wealth, institutional money and private equity investments.

On the labour market front, the National Education Policy 2020 has given the scope for foreign universities to have an equal footing in the Indian higher education space. Offering equity-linked incentives, a PPP model can be adopted for setting up centres for hotel management by engaging industries and universities rich in endowment. Backstopped by government guarantees, international investors and academic institutions would gain the necessary confidence to step up investment and commit for the long haul. Furthermore, giving a helping hand to companies that are keen to set up and operate infrastructure, the state can build up and release land banks on long leases, thereby reducing the upfront cost for investors.

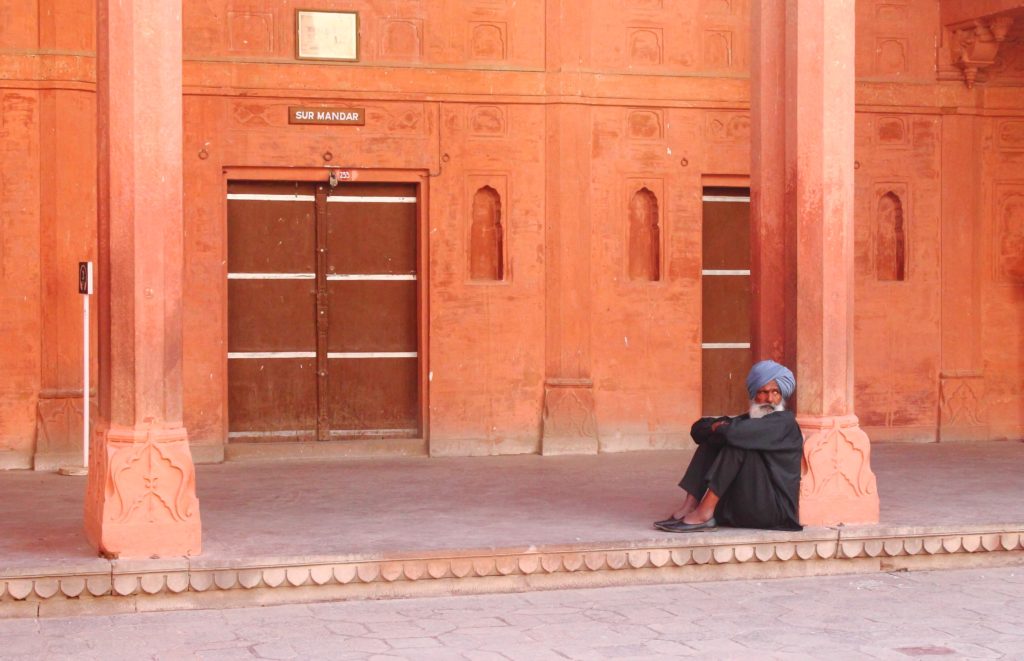

Photo by Ariel Pilotto

Also Read: The Covax Exchange: Gavi’s plans to let countries trade in vaccines

Also Watch: Book Discussion | The India Way: Strategies for an Uncertain World

Disclaimer: Views expressed in the blog are the author's own

A superb and very nuanced analysis of bottlenecks in the process of tourism development.At the same time ,a detailed roadmap including the internship for school leavers is provided which should attract the attention of policy makers